Raising Co-Pays On Low-Income Beneficiaries' Drugs Not A Solution

By John McManus, The McManus Group, jmcmanus@mcmanusgrp.com

Raising the cost of a good or service results in less consumption of that good or service. That fundamental economic principle makes it hard to understand why the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC), which advises Congress on Medicare payment policy, has recommended increasing cost-sharing on low-income Medicare beneficiaries for their brand name drugs dispensed through the Part D program.

Raising the cost of a good or service results in less consumption of that good or service. That fundamental economic principle makes it hard to understand why the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC), which advises Congress on Medicare payment policy, has recommended increasing cost-sharing on low-income Medicare beneficiaries for their brand name drugs dispensed through the Part D program.

MedPAC proposes doubling co-pays for preferred brand name drugs from about $3 per prescription to over $6, on the argument that low-income subsidy (LIS) beneficiaries – those with incomes below $17,000 — do not have sufficient incentives to choose generic drugs. But that premise is unfounded: Generic utilization between LIS beneficiaries and non-LIS beneficiaries is similar — 75 percent versus 79 percent in 2011 (the most recent year data is available). And generic utilization has soared for both groups since the inception of the Medicare drug benefit.

The real impact would be less patient adherence to needed drugs that do not yet have a generic substitute on the market. Harvard economist Michael Chernew (now vice chairman of MedPAC) published a study a few years ago that demonstrated medication adherence is more likely to decline when co-payments increase for individuals in low-income areas. Since considerable research suggests that adherence to medications is an important driver of good clinical outcomes and key driver of total costs, for patients with chronic diseases, Chernew concludes that “increases in patient out-ofpocket expenditures for prescription drugs is likely to exacerbate health disparities.”

Even small increases in cost-sharing can significantly reduce prescription drug adherence for low-income beneficiaries for two reasons:

- Low-income beneficiaries tend to be sicker and therefore need more prescription drugs.

- Any cost increase for patients with very limited resources makes it much more likely they forgo their prescriptions because they are least able to afford them.

Whether patients should be dispensed a generic drug when a physician prescribes a substitutable brand-name drug is not really in debate. A more complicated challenge is whether a patient should be coerced into taking a generic drug in a therapeutic class when the prescribed brand-name drug has no generic available.

For example, although most drug classes for treating psychiatric conditions include generics, beneficiaries with these conditions are particularly vulnerable to treatment disruptions. A study by Morden et al. published in Health Affairs found that “In treating mental illnesses, patients and physicians typically work through trial-and-error processes to identify the best medication or medication combination.” As such, formulary enforcement that requires patients to be switched off a brand-name drug that is working for them to a chemically different generic drug would create serious safety and efficacy concerns.

For decades the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) adopted a static view of preventive benefits when evaluating the fiscal impact of legislation. For example, CBO only counted the increased costs of covering prescription drugs when Medicare Part D was enacted and making preventive benefits free when the Affordable Care Act was enacted. The reduced costs or savings from keeping patients on drug regimens and out of hospitals and other acute settings was not considered.

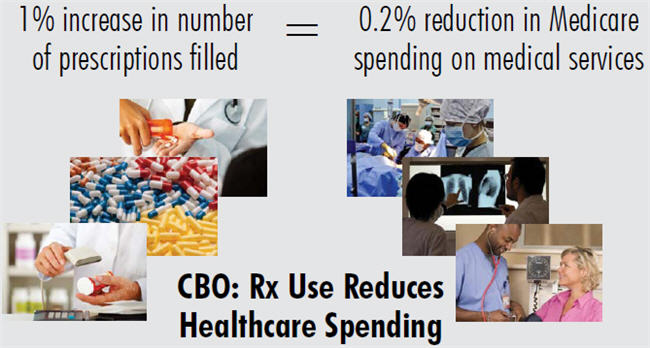

A sea change occurred in November of last year, when CBO released a pivotal white paper which acknowledged that a 1 percent increase in the number of prescriptions filled by beneficiaries would cause Medicare’s spending on other medical services, such as hospital care, to fall by roughly onefifth of 1 percent. Conversely, a policy that resulted in a drop in prescriptions filled would result in a medical cost increase of the same proportion. The estimate applies only to policies that directly affect the quantity of prescriptions filled.

Raising co-pays on low-income beneficiaries for their brandname prescription drugs should certainly trigger this more dynamic view of the world! Thus, increasing LIS co-payments would not only put safety of low-income patients at risk but result in higher medical spending per Congress’ official scorekeeper.

What Are The Alternatives To Produce Savings From Drugs Provided To LIS Beneficiaries?

The Obama Administration has proposed applying Medicaid rebates to drugs provided to LIS Medicare beneficiaries. As I detailed in a previous column, this would undermine the market forces that have successfully controlled cost in Part D, result in pricing distortions and cost-shifting to employers, veterans, and other groups, and could result in shortages seen in other parts of Medicaid.

A preferable solution to either higher cost-sharing for LIS beneficiaries or Medicaid rebates on that population would be to strengthen the competitive forces that have already contained costs in Part D.

Currently, Part D plans receive a full subsidy up to the average bid of all plans in a Part D region. That means plans can maximize their revenue if they bid at or just below the average. They lose potential revenue if they bid below the area benchmark and lose their opportunity to cover these beneficiaries if they bid above the benchmark. But this formula has resulted in shadow pricing, where plans bid as close to the benchmark as possible without exceeding the benchmark.

Congress could make the LIS program far more efficient if it rewarded plans for bidding low. For example, it could auto-assign more LIS beneficiaries to the plans with the lowest bids; e.g. 50 percent for the cheapest plan, 30 percent for the second cheapest plan, and, 20 percent for the third cheapest. Presently, beneficiaries who do not affirmatively select a plan are auto-assigned randomly, and there is little incentive to bid low and deliver healthcare more efficiently.

The old ways of approaching healthcare policy no longer work. Conservatives generally would like to impose more cost-sharing so there is more “skin in the game.” Liberals look to price controls, such as arbitrary Medicaid payment rates (i.e. rebates).

Competition is a better solution. Congress should be more creative in unleashing competitive forces so that beneficiaries and taxpayers alike can benefit from a more efficient system.

John McManus is president and founder of The McManus Group, a consulting firm specializing in strategic policy and political counsel and advocacy for healthcare clients with issues before Congress and the administration. Prior to founding his firm, McManus served Chairman Bill Thomas as the staff director of the Ways and Means Health Subcommittee, where he led the policy development, negotiations, and drafting of the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003. Before working for Chairman Thomas, McManus worked for Eli Lilly & Company as a senior associate and for the Maryland House of Delegates as a research analyst. He earned his Master of Public Policy from Duke University and Bachelor of Arts from Washington and Lee University. He can be reached at jmcmanus@mcmanusgrp.com.