Enactment Of Site-of-Service Neutrality Could Open Door For 340B

By John McManus, president and founder, The McManus Group

I have written a lot about the ill effects provider consolidation has on competition and patient choice. But Congress made an interesting move recently when it enacted the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 in November. It made hospital acquisition of physician practices and competing ambulatory surgery centers (ASCs) less financially appealing. And in doing so, Congress illuminated a possible path to reform 340B, the pharmaceutical pricing scheme for certain nonprofit hospitals that has ballooned in recent years.

I have written a lot about the ill effects provider consolidation has on competition and patient choice. But Congress made an interesting move recently when it enacted the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 in November. It made hospital acquisition of physician practices and competing ambulatory surgery centers (ASCs) less financially appealing. And in doing so, Congress illuminated a possible path to reform 340B, the pharmaceutical pricing scheme for certain nonprofit hospitals that has ballooned in recent years.

For several years, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) and the Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General (OIG) have opined that hospitals should not receive inflated payments from Medicare for physician and outpatient surgical services that are paid a fraction of the amount to independent physician practices and ambulatory surgery centers in the community.

- MedPAC found that over the past seven years outpatient services increased by 33 percent in hospitals, and this “growth, in part, reflects hospitals purchasing free-standing physician practices and converting them into hospital outpatient departments [HOPDs].”

- MedPAC also documented substantial shifts in market share in high-cost cardiology services from the physician office setting to hospitals — driving costs higher for patients and the program because of the higher reimbursement levels at hospitals for the identical services.

- MedPAC recommended cutting hospital payments for evaluation and management codes to the physician office level, which would save the program more than $10 billion over the next decade.

Meanwhile, the OIG recommended reducing hospital payments for lowrisk, outpatient surgical services commonly performed at ASCs to the ASC rate, which it estimates would save Medicare $15 billion over five years and beneficiaries another $2 billion to $3 billion in lower copayments. As a result, payments for a colonoscopy would drop from about $1,400 to $630, and cataract surgeries would fall from $1,745 to the ASC rate of $976. OIG concluded that it was irrational to pay almost twice the amount for a procedure commonly performed in the community setting at the most expensive site of care.

But, until November’s budget bill, the powerful hospital lobby had successfully swatted away such proposals, arguing that those swollen fees were necessary to ensure patient access. Thomas Nickels, executive VP of government relations and public policy for the American Hospital Association (AHA), commented that a site neutrality policy “may endanger patient access to care, especially among patients who are sicker, the poor, minorities, and seniors who often receive care in hospital outpatient departments.”

Wait — access to care for vulnerable populations would be endangered because patients received that care at an independent physician practice or at a hospital-acquired practice that will be paid at physician office rates? Why is that? They don’t say.

But rather than take the AHA head-on, Congress enacted a provision that prospectively limits reimbursements of services to the physician office or ASC level for future hospital acquisitions. In essence, the policy permits hospitals to keep what they have but arrests future windfalls. Under the policy, hospitals can continue to acquire physician practices and outpatient surgery centers, but can no longer reap the excessive payment rates when those community providers (often located miles away) are absorbed by hospitals. The Congressional Budget Office scored the provision as saving $7.9 billion over 10 years — that is a lot of forgone windfalls!

This policy alone, of course, will not halt hospital acquisitions of physician practices. Those acquisitions may continue for reasons related to increased market power and the capture of referrals for ancillary services, but at least Medicare’s role in fueling those acquisitions will be terminated.

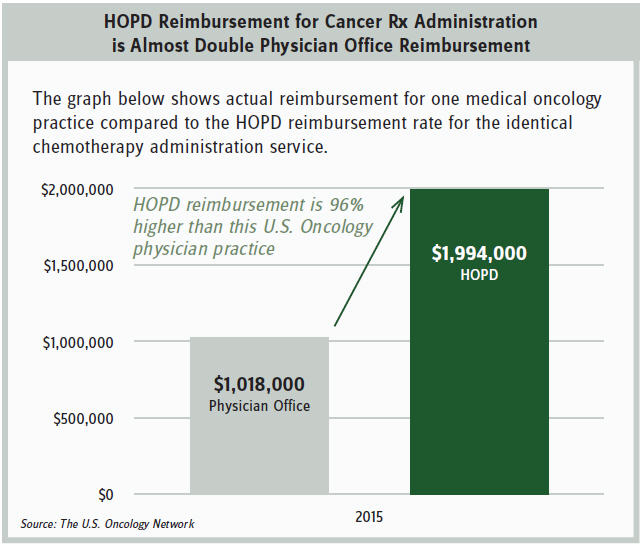

The policy should help slow the growth of the 340B program. A recent Moran Company study commissioned by The U.S. Oncology Network found that Medicare pays about twice as much to hospitals than to freestanding oncology practices for the identical chemotherapy administration. (See attached table showing Medicare reimbursement to an actual physician practice and what that reimbursement would have been to a hospital for the identical services.)

It is no wonder that hospitals are acquiring oncology and other physician practices at such a rapid pace. According to a 2014 Berkeley Research Group report, 340B DSH (disproportionate share hospital) hospital acquisitions of community oncology practices increased more than eightfold from 2004 to 2011. The Moran Company found hospital outpatient market share of chemotherapy administration skyrocketed from 13.5 percent in 2005 to 33 percent in 2011. (More recent statistics are not available, but that escalation continues unabated.)

Of course, hospital acquisition of physician practices is only one reason for the growth of the 340B program. Between 2003 and 2013, the volume of 340B revenue nearly tripled to $7.5 billion. From 2005 to 2010, the number of hospitals in the 340B program grew 134 percent from 583 to 1,365 and from 2010 to 2014 grew another 57 percent to 2,140 covered entities. At the same time, the number of 340B entities contracting with retail pharmacies has soared to more than 3,000 this year from just 1,000 in 2010.

For the past several years, the pharmaceutical industry has been focused on fundamental reform of the 340B program — narrowing the definition of the patient to uninsured or indigent individuals, prohibiting contracting with multiple off-site pharmacies, limiting 340B revenue for prescriptions to Medicare beneficiaries, among other reforms. But those efforts have run into a brick wall — the powerful hospital lobby with active constituents in every member’s district. In addition, the political environment has become more toxic for the pharmaceutical industry, with increased scrutiny of pharmaceutical pricing.

So perhaps a new strategy based on the recently enacted site-of-services reform may be worthy of contemplating? Apply a moratorium to arrest further 340B growth until Congress can develop consensus on a more fundamental reform. Such an approach could entail any or all of the following elements:

- Prohibit the addition of any new 340B DSH hospitals.

- Prospectively prohibit physician practices acquired by 340B hospitals from accessing 340B prices (consistent with definitions in the Bipartisan Budget Act).

- Prohibit the addition of any “child sites” of existing 340B DSH hospitals.

- Prohibit addition of any off-site pharmacy (including mail-order) of any 340B DSH hospital.

Of course, pharmaceutical industry consensus is needed on any proposal — whether fundamental reform or more modest steps such as transparency of how hospitals are using 340B revenue or a moratorium — as legislators are unlikely to engage on a solution that cannot find broad support. A strong policy case can be made for fundamental reform of the 340B program, particularly in the wake of the draft guidance issued by HRSA (Health Resources and Services Administration) in August which validated the need for greater oversight and control of the 340B covered hospitals. But healthcare policy is often made by crosswalking a successful approach in one sector to a different sector.

The new year provides an opportunity to float new ideas and approaches. Inaction is no longer a viable option.