Congress' Abdication Of Authority Of Medicare To The Executive

By John McManus, president and founder, The McManus Group

Six years after the enactment of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), policymakers are just beginning to appreciate a little-known provision that essentially outsources Congress’ authority over Medicare to the executive branch. While the Republican Congress launched fusillade after fusillade against unpopular aspects of Obamacare — the individual mandate, death panels (aka the Independent Payment Advisory Board), illegal funding schemes to prop up the exchanges, and new healthcare taxes — a much more sinister power center was emerging.

Six years after the enactment of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), policymakers are just beginning to appreciate a little-known provision that essentially outsources Congress’ authority over Medicare to the executive branch. While the Republican Congress launched fusillade after fusillade against unpopular aspects of Obamacare — the individual mandate, death panels (aka the Independent Payment Advisory Board), illegal funding schemes to prop up the exchanges, and new healthcare taxes — a much more sinister power center was emerging.

The ACA established the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) to “test” new delivery models intended to better coordinate care, improve outcomes, and contain costs. That prima facie description sounds reasonable enough, but Congress is now learning that the new agency can preempt, ignore, and override long-standing statutory provisions through nationwide “demonstrations” that Congress has little ability to alter or halt.

The ACA provided an astounding $10 billion a decade, forever, in automatic funding for the new agency. The administration acquired a building for the new agency a few miles down the road from the CMS suburban Baltimore headquarters. And for the first few years, the CMMI’s rather academic staff toiled in relative obscurity, commissioning studies and RFPs to their ivory-tower colleagues, and initiated voluntary coordinated care demonstrations.

THE ACO FAILURE

Central to the Obama administration’s CMMI efforts was creating and promoting accountable care organizations (ACOs) — mostly hospital-led providers tasked to better coordinate care and ostensibly control costs. By 2015, there were nearly 470 ACOs enrolled in either the Medicare Shared Savings Program or Pioneer ACO Program and serving nearly 8.9 million Medicare beneficiaries.

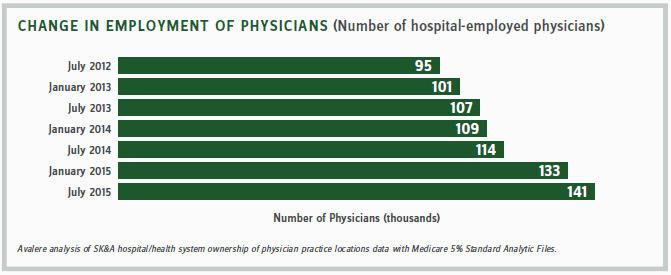

Establishment of these ACOs fueled provider consolidation by strengthening mega-hospital systems’ leverage in negotiating buyouts of independent physician practices, ambulatory surgery centers, and other outpatient providers that served as alternative access points for patients and an important competitive counterbalance for the delivery of care. Physician practices and other community providers were threatened with being frozen out of markets if they did not join up with dominant hospital systems embarking as an ACO. A September 2016 Avalere study found that between 2012 and 2015, hospitals acquired 31,000 physician practices, and the number of hospital-employed physicians increased by almost 50 percent.

But how did the ACOs fare in delivering higher quality and reducing costs? Poorly. In August, CMS released the 2015 financial and quality performance results and found that 48 percent of Medicare ACOs produced no savings and 69 percent did not produce enough savings, for bonuses in 2015. Moreover, the Medicare Shared Savings Program racked up a net loss of $216 million in 2015, after counting both bonuses and losses — not a huge number, but certainly nothing to make one think the CMMI will bend the cost curve in Medicare. A final dagger to the heart was the announced withdrawal of Dartmouth-Hitchcock from the ACO program, as Dartmouth researchers were key architects of the program.

REAL CMMI POWER REVEALED IN PART B DRUG DEMO

While this voluntary program appears to be a dud, the full scope of the CMMI’s power came into view when it proposed a nationwide, compulsory five-year “demonstration project” regarding physician-administered drugs that would substantially cut reimbursement for expensive Part B drugs and later test “value-based purchasing” schemes, including reference pricing.

As stakeholders and Congress absorbed the implications of the proposal, it became crystal clear that this was unlike any Medicare demonstration project seen in the past — typically limited to several discrete geographical locations and populations and requiring explicit congressional approval before it could be implemented on a broader scale. The CMMI demonstration applied to all Part B products and all physicians and patients in three-quarters of the country. The ACA statute does not limit the scope of a CMMI demonstration in any way, and, in fact, it authorizes successful demonstrations to be expanded nationwide and made permanent without congressional assent. It also explicitly permits the CMMI to waive any statutory provision in Medicare, Medicaid, and associated fraud and abuse laws.

More than 300 patient and provider groups and a slew of bipartisan letters from hundreds of members of Congress objected to the far-reaching scope and substance of the demonstration. But we’ve now heard that the CMMI is determined to go forward with the proposal, though a final version has not yet been published. The CMMI statute denies stakeholders recourse in the administrative process or in the courts. Its proposals are protected from administrative and judicial review.

WHAT CAN CONGRESS DO?

Can’t Congress legislatively alter or repeal a CMMI demonstration or the underlying authority provided to the CMMI? As it turns out, that will be most difficult.

In a seminal hearing in September, the House Budget Committee learned that the legislative branch’s own budget analysts — the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) — were in the tank for the administration in regard to the CMMI’s ability to save Medicare costs, notwithstanding the clear evidence of failure of ACOs, by far the largest demonstration undertaken by the agency. In fact, the CBO projects the CMMI will save a staggering $45 billion over the next 10 years, or a net $34-$35 billion over that time period. Based on what? The CBO witness could not explain to Chairman Price (R-GA), the methodology and formulas behind this gargantuan and baseless estimate.

But the CBO did make it clear that any provision that repeals, constrains, or otherwise hampers the CMMI’s authority to test demonstrations would be assessed with a loss of savings. As Chairman Price stated, “This makes it virtually impossible for Congress to change policy and have it be seen as ‘right’ from a budgetary standpoint.” If Congress blocked the Part B drug demonstration, that several-billion-dollar cost would have to be offset with a provision that cuts Medicare spending by an equal amount. However, nothing would prohibit the CMMI from issuing the identical or even more onerous demonstration with larger cuts applying to greater populations, immediately after Congress enacted the bill. As such, Congress has lost control over its own baseline and ability to oversee and manage the Medicare program.

The executive branch would be in full control because Congress would be required to cannibalize cherished programs and protections simply to preserve current policy that blocks the CMMI demonstrations, which override long-standing statutory law carefully negotiated by Congress — the people’s representatives.

The end results of this are ominous indeed. The executive branch does not need congressional input and assent in making Medicare policy; the CMMI can do that on its own. Moreover, once issued by the CMMI, Congress has little ability to alter or halt that policy, no matter how pernicious.

Should we be more concerned with the constitutional abdication of power to the executive branch or the devious schemes being concocted on Medicare Part D and other sacred programs by leftists hoping to join a new Clinton administration?