The Looming Battle Between The Pharmaceutical And Health Plan Industries

By John McManus, president and founder, The McManus Group

Although generic utilization has never been higher — a new report by the IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics notes that 86 percent of all prescriptions filled were generic and more than half of prescriptions cost patients on average less than $5 out-of-pocket — the growing cost of specialty medicines is sparking a marketing and policy battle between the pharmaceutical industry and plans that cover those drugs.

Although generic utilization has never been higher — a new report by the IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics notes that 86 percent of all prescriptions filled were generic and more than half of prescriptions cost patients on average less than $5 out-of-pocket — the growing cost of specialty medicines is sparking a marketing and policy battle between the pharmaceutical industry and plans that cover those drugs.

That same report found that just 2.3 percent of prescriptions accounted for 30 percent of all out-of-pocket costs, including 17 drugs that were launched last year for orphan diseases with small populations of patients (less than 200,000). Specialty medicine costs grew by 14 percent last year and are projected to climb 63 percent by the end of 2016, in part because of breakthrough treatments for Hepatitis C, a disease that affects 3.4 million patients.

Express Scripts, a pharmacy benefit manager that processes more than 1 billion U.S. prescriptions annually, urged its insurance and employer clients to join a coalition to stop prescribing Sovaldi, a breakthrough for Hepatitis C, once competitor products hit the market unless the sponsor company, Gilead, lowers its price. Merck, AbbVie, and Bristol-Myers Squibb are currently in clinical trials in the therapeutic space, but their pricing decisions remain unclear at this time. Steven Miller, Express Scripts' chief medical officer, said, “What they have done with this particular drug will break this country.”

Break this country? Sounds like hyperbole. However, that perspective may be understandable from an entity whose sole job is managing one silo of healthcare spending with no appreciation or recognition of the enormous savings that drugs can deliver to overall medical costs or health outcomes. Hepatitis C infections kill 15,000 patients a year and are a leading cause of liver transplants, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. A liver transplant costs $175,000 or more, twice the cost of a Sovaldi regimen.

Hepatitis C is a smoldering disease with symptoms that are often not recognized for decades but can cause liver damage, cirrhosis, and liver cancer, which often requires a liver transplant or results in death. The disease is particularly prevalent in Baby Boomers, comprising 75 percent of Hepatitis C infections, of which one million will qualify for Medicare in the next 10 years. Sovaldi proponents note that it is comparably priced to the now-obsolete regimen of a dozen-pills-aday- plus interferon that has a lower cure rate (75 percent vs. Sovaldi’s 90 percent) as well as poor adherence because of the miserable side-effects of interferon injections that inflict flu-like symptoms during the months of treatment.

But that’s not deterred the nemesis of the brand-name pharmaceutical industry, Energy & Commerce Committee ranking member Henry Waxman (D-CA) and his Democratic colleagues on the committee, from issuing a sternly worded letter to the CEO of Gilead demanding he justify the cost of the $84,000 treatment. While the retiring Waxman lacks the clout he once had, that letter sent the entire biotech sector’s market value plummeting upon its release. Investor unease about possible price controls or pressure to restrict access sent many out of the stocks, believing their steady upward climb might be a bubble waiting to burst.

Express Scripts' treatment of Sovaldi is typical of a trend toward noncoverage, which now includes a list of 44 drugs, such as Novo Nordisk’s two top drugs, Victoza and Novolog, and Pfizer’s Xeljanz. CVS Caremark, a major competitor to Express Scripts, also blocked treatment to 34 therapies last year and intends to expand the list. Molina, the largest Medicaid managed care plan, is trying to reserve coverage of Sovaldi and other specialty pharmaceuticals for only its sickest patients.

The battle over these products has spilled into policy debates in Washington. Health plans and PBMs (pharmacy benefit managers) were behind an effort to encourage CMS (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services) to eliminate access protections to three of the six protected classes — antipsychotics, antidepressants, and immunosuppressives — arguing that covering substantially all drugs in those therapeutic classes was costing Medicare $4.2 billion. A fusillade counter by patient groups, pharmaceutical companies, and other stakeholders forced CMS to withdraw that proposal in its entirety.

Plans also attempted to eliminate the science-based USP Pharmacopeia Convention from its role in defining therapeutic classes for purposes of establishing “Essential Health Benefits” in Obamacare plans, preferring those classes to be determined by the plans themselves. That proposal was rejected by Health and Human Services. But plans succeeded in limiting coverage requirements to one drug per class, unlike Medicare Part D’s standard of two drugs per class, much to the pharmaceutical industry’s chagrin.

Meanwhile, the chatter in Washington is that America’s Health Insurance Plans (AHIP), having successfully beat back pending cuts to the Medicare Advantage program, is now focusing on specialty product cost challenges to its Medicare and Medicaid plan members. Some plans are asserting they cannot absorb the cost of specialty products like Sovaldi because rates were established before the drug was launched.

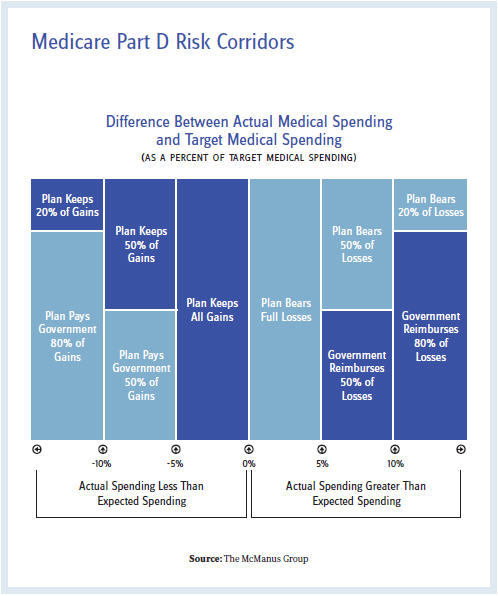

In actuality, Medicare Part D is well equipped to absorb the costs and fundamentally protect the plans through the automatic stabilizers built into the program. The plans are responsible for only 15 percent of the costs an individual beneficiary consumes above the catastrophic threshold, with the federal government paying 80 percent in reinsurance and the remaining 5 percent as co-insurance by the beneficiary. In addition, plans are protected for aggregate expenditures that exceed target costs through “risk corridors.” Under the risk corridor program, Medicare reimburses plans for 50 percent of losses between 5 percent and 10 percent of the target and 80 percent of losses above 10 percent of the target. The mirror image applies as well for profits that exceed the target.

Historically, risk corridors have required plans to pay back excessive profits instead of being insulated from excessive costs. The 2013 Medicare Trustees Report documented net risk-sharing payments of $900 million for the 2011 plan year, $700 million in net payments for the 2012 plan year, and $1 billion for the 2013 plan year. In other words, plans have ample latitude to absorb additional costs.

CMS possesses the authority to increase risk-adjusted payments to plans for certain medical indices, which could be an area pharmaceuticals and plans could collaborate to enhance. But those payments are based on claims data, which means that there would be a 2- to 3-year time lag until these higher payments could be realized.

For years the pharma industry has been accused of producing too many “me-too” drugs. But the industry’s success in producing innovative products that address unmet medical needs is raising the ire of certain payers that are tasked with controlling pharmaceutical spend but are not accountable to overall medical spend or health outcomes. After a relative period of détente between the pharmaceutical and health plan sectors, a lobbying battle between these two titans could become more intense.