Educating Consumers About The Risks Of Counterfeit Medicines

By Camille Mojica Rey, Contributing Writer

Follow Me On Twitter

This is the final article in a four-part Life Science Leader series examining the current state of the counterfeit medicines problem. Previous stories looked at efforts to quantify the crime, examined the issue from the perspective of industry giant Pfizer, and described what is being done by an international coalition to fight the crime.

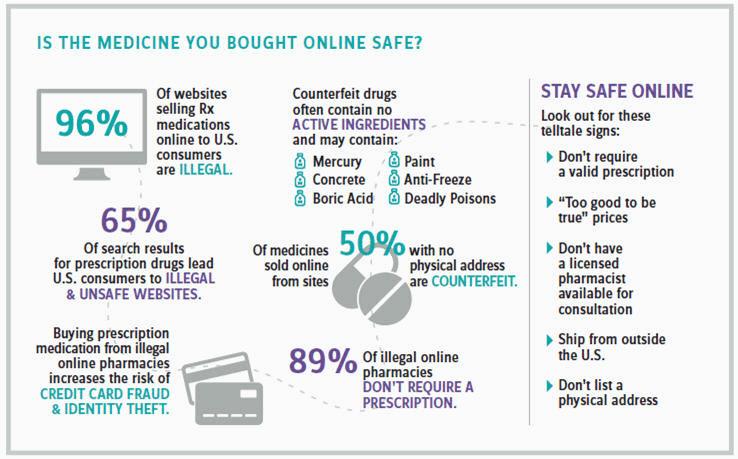

In 2016, the Alliance for Safe Online Pharmacies (ASOP Global) estimated that 20 rogue online pharmacies are launched every day. Unsuspecting patients do not realize that 96 percent of these sites are bogus. They risk their health if the pills have no active ingredients or contain deadly ingredients. They put themselves at risk of identity theft. They also unknowingly fund organized crime and terrorists.

The pharmaceutical industry has created or joined numerous local, national, and international partnerships to combat the problem of rogue pharmacies. Their partners include the likes of large corporations, such as Google and Microsoft, as well as pharmacy groups, medical associations, and patient advocacy groups.

“I see improvement in industry efforts to stop counterfeiters, but I don’t see improvement in results,” says Marvin Shepherd, president of the Partnership for Safe Medicines (PSM) and professor emeritus at the University of Texas at Austin’s School of Pharmacy. PSM and other organizations like it have been working to teach people how to safely buy drugs online and identify illegal online pharmacies and point them to programs that help pay for their medicines so they don’t go looking for them online.

These nonprofit groups have their work cut out for them. A 2015 study by pharmaceutical giant Sanofi estimated that 88 percent of Americans were unaware of the dangers of counterfeit drugs. Nonprofits working to educate the public have been busy producing awareness campaigns, building educational websites geared for patients, and targeting advertising to consumers through search engines.

In 2014, the National Association of Boards of Pharmacy (NABP) started making it easier for consumers to find legitimate pharmacies online by launching .pharmacy as a Top-Level Domain (TLD). NABP evaluates these sites and certifies those that are found to be in compliance with pharmacy laws and meet standards for pharmacy practice, as well as patient safety.

A NEW WAY TO REACH CONSUMERS

The challenge for NABP and others is to get their message out so that patients understand the risks and know how to stay safe online. ASOP Global has taken many traditional approaches to reaching consumers, including social media and placing a television PSA in New York’s Times Square. “None of it has been enough,” says Libby Baney, ASOP Global’s executive director.

ASOP Global is trying a new way to reach patients: targeting their doctors, nurses, and pharmacists instead. “Healthcare providers are critical to the education of healthcare consumers,” Baney says. However, according to data collected by ASOP Global in 2016, only 6 percent of providers surveyed ever discussed the risks of rogue online pharmacies with their patients, and nearly 95 percent of them did not know how to identify illegal online drug sellers.

In 2015, ASOP Global and the Federation of State Medical Boards (FSMB) launched a program that includes a free continuing education course, “Internet Drug Sellers: What Providers Need to Know,” for doctors, nurses, pharmacists, and other healthcare providers. “ASOP Global hopes to educate providers about the dangers of illegal online pharmacies so they, as the most trusted resource to patients, can help consumers avoid the health and financial risks associated with buying counterfeit products online,” Baney says. Pilot studies showed that 81 percent of healthcare providers who took the course said they would now include discussions of the risks posed by rogue online pharmacies with their patients.

In December, ASOP Global launched www.BuySafeRx. pharmacy, a site where providers, patients, and caregivers can quickly verify whether an internet pharmacy website is safe and legal. The organization has also partnered with the American Medical Association, American Pharmacists Association, and 14 other national nonprofit organizations to deliver educational materials and content to offices through websites and on social media. “We are looking for the best ways to reach providers,” Baney says.

ADAPTING TO NEW THREATS

Raising awareness among physicians goes beyond educating them about online risks so that they can inform patients. Doctors also need to know that there are criminals posing as patients. “What happens is that consumers will sell leftover drugs — or ones they never needed in the first place — to diverters,” PSM’s Shepherd says. Diverters repackage pills, sell them locally, or send them to a fraudulent wholesaler. Once they are repackaged, the drugs are considered counterfeit. The diverter stands to make $500 on the same prescription that cost the person posing as a patient $20 or $30.

In 2012, PSM published online toolkits for both healthcare providers and patients. The one for healthcare providers gives tips on spotting counterfeits, looking into the possibility that drug treatments are not working because they may be fakes and educating patients about the risks of online pharmacies. Future efforts by PSM and others will have to include educating doctors on new ways they may be targeted by criminals, Shepherd says.

The global use of unique identifiers is expected to be in place in the next few years. These bar codes will help combat pharmaceutical crime at all levels of the supply chain, but they will not be enough, Shepherd says.

Emerging technology that would allow the marking of individual pills may be the answer. Such methods are worth investigating, Shepherd says, because pharmaceutical crime is here to stay. “What you have to do is try to control it. You have got to stay one step ahead of the thugs.”