Beyond IPOs: Alternative Funding Options For Biotech Startups

By Rob Wright, Chief Editor, Life Science Leader

Follow Me On Twitter @RfwrightLSL

“While it is great when Morgan Stanley, JP Morgan, and Goldman are fighting to take your company public, sometimes, given the investment environment, you have to play in a ‘less elegant’ part of the finance swimming pool (e.g., Form 10s and reverse mergers).” This statement by Aftab Kherani, M.D., a partner at Aisling Capital, was made in response to the question, “What are some of the more innovative ways companies are using to raise money,” in a Q&A published in Life Science Leader magazine. It seems that not every company is going to garner the glitz and glam usually associated with taking a company public via a traditional IPO (i.e., Alibaba bringing in $26 billion). That being said, it seems important for entrepreneurs to keep in mind their end goal — getting their biopharmaceutical startup actually started up. And though the pros and cons of funding opportunities like Form 10s and reverse mergers might be “old hat” for a financial expert like Kherani, we thought, given the recent slowdown in the IPO market, it might be a good opportunity to explore why Form 10s and reverse mergers merit deeper exploration.

What Is A Form 10 And Why Choose It Over A Traditional IPO?

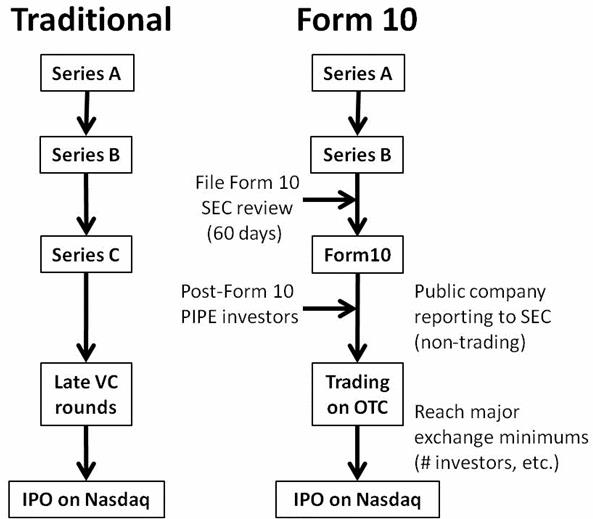

A Form 10 filing is used by private companies to register a class of securities with the SEC. It includes the type and amount of security being issued, but it should be noted that these securities do not need to be publically traded. According to David Thomas, CFA, senior director of industry research and policy analysis at BIO, a company can voluntarily file a Form 10, and after a 60-day SEC review period, have the necessary requirements to publish 10K, 10Q, and 8K documents like any publically traded company. Once a Form 10 is in effect, institutional public equity funds restricted from investing in private companies can invest in these public, not-yet-traded securities. While the structure of the transaction is similar to a PIPE (Private Investment in Public Equity), it differs in that there is not a traded-price quote that can be referenced. Once investors have valued the Form-10 company, the enterprise can float securities on the OTC (over-the-counter) exchanges, where retail investors can acquire shares. After the investor base reaches a specified amount and the company has been in existence for greater than two years, an IPO can be conducted on a larger exchange (e.g., NASDAQ, NYSE). Taking this alternate route allows startups to address two big biopharmaceutical financial marketplace issues — constricted venture funding and lackluster IPOs.

Though the retail “day-of” pricing in a traditional IPO makes for a lot of investor uncertainty, the Form 10 offers a clear path as to how much will be raised and with what institutional funds. Another benefit of going the Form 10 route is that there is a price range established before reaching an IPO. Finally, Form 10s opens up a private company to a new set of investors (e.g., firms restricted to public-only investments). According to Thomas, the Form 10 is appropriate for high-quality companies that have a strong story and willing long-term investors. That being said, the Form 10 approach will not work if there isn’t interest among retail buyers once the IPO eventually launches. To increase awareness among retail buyers, company management must be willing to build relationships with the buy-side in advance of the Form 10 filing.

While it is difficult to find a list of companies that started out via the Form 10 route, there are plenty of companies that can boast from having been started in garages. And though starting a biopharma in a basement or garage is probably a label most biopharmaceutical entrepreneurs strive to avoid, one thing that shouldn’t be avoided is the possibility of using a Form 10 to get a biopharmaceutical startup off the ground.

Diagram Of Tradition IPO Versus Form 10 Route

Source: The IPO Road Less Traveled: Form 10, by David Thomas, CFA, BIOtechNow, February 25, 2013.

What About A Reverse Merger As A Means Of Funding A Startup?

A reverse merger is the acquisition of a public company, usually a dormant shell (i.e., has no or nominal business operations or noncash assets for an extended period of time). Long out of favor, the reverse merger does have some advantages (e.g., avoids the IPO process and associated costs, enables a startup to quickly get on a public exchange). And while a reverse merger can be a great way to raise money through the sale of stock on a public market, Martin Zwilling, a startup expert who has written two books and more than 500 articles on the subject, says there are at least six challenges to consider before trying.

- Make sure the shell chosen is squeaky clean. The image of a shell company can be something that sticks with you, and can either come with brand equity or baggage (e.g., tarnished by stories of shareholder lawsuits and “pump-and-dump” schemes). Zwilling recommends only working with financial and broker organizations (with a track record of success) so they can do the required due diligence.

- Getting into the game takes real money. Depending on the shell company, there is a cost associated with acquiring a controlling interest in this public company. In addition, there are other costs associated with navigating the reverse-merger process (see video of reverse merger explanation). And while less complicated and less expensive than a traditional IPO, executing a reverse merger can easily exceed a half-million dollars. As such, the reverse-merger approach is not for entrepreneurs already out of money.

- Being a public company is neither cheap nor easy. For a startup to be ready to play in the corporate world it should: be an established company; have millions of dollars in annual revenue; have profits; and follow generally accepted accounting, reporting, and auditing procedures. Just the burden of being a public company can reach a million dollars per year.

- Increased jeopardy and less fun for the entrepreneur. The increased exposure and opportunity of a public company comes with a higher risk. Regulatory mistakes and non-compliance can result in severe civil and criminal penalties for executives and board members of public companies, not to mention significant public scrutiny (e.g., Martin Shkreli).

- Reverse mergers may not get your startup on the NADSDAQ. Most public shells ready for sale are not listed on a national securities exchange, but traded on the OTC Bulletin Board. While these can be renamed and moved, doing so may negate the cost and time advantages originally sought.

- Can your team motivate shareholders? The process of doing a reverse merger doesn’t raise any capital. As such, reverse mergers still require a business team and a story that continually motivates stock brokers and public stockholders. Further, being a public company means you may no longer have the option of investing all earnings back into growth or servicing a special corporate cause.

That being said, Zwilling reminds that reverse mergers are not all bad, and notes this was actually how the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) went public in 2006. Some believe reverse mergers may soon become the preferred IPO approach for emerging high-growth operations and already seems preferred by Asian companies wanting to go public in the U.S. Other than raising money, the reverse merger may be the quickest way to obtain the benefits of being a public company (e.g., employee stock options, using liquid shares to purchase other companies, credibility, etc.).

Whether going public via a Form 10, reverse merger, or the traditional IPO route, none should be viewed as a simplistic process just to fund your startup. These are strategic decisions. Although each may attract more funding, it is likely that all will change the culture and focus of a company, as well as the role of its founder — from entrepreneur to corporate exec.